Newman, Rachel and Howard Davis, Christine and Leech, Roger (2022) The Early Medieval Site at Dacre, Cumbria. UNSPECIFIED. Oxford Archaeology Ltd, Lancaster.

![[thumbnail of Dacre Cover]](http://eprints.oxfordarchaeology.com/6183/1.hassmallThumbnailVersion/Dacre_Cover.jpg)

Dacre_Cover.jpg

Available under License Creative Commons Attribution.

Download (595kB) | Preview

Appendix_01_L11387.pdf

Download (121kB) | Preview

Appendix_02_L11387.pdf

Download (2MB) | Preview

Abstract

St Andrew’s Church, Dacre (NY 460 266), is one of those rare early medieval sites in being associated with a documentary reference verifying its existence and character. In the Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum, completed in 731, the Venerable Bede records a miracle taking place in a monastery built by the River ‘Dacore’ and taking its name from the same. There, a monk was cured of blindness by a miracle enacted by the hair of the dead St Cuthbert, which was clearly being stored at the site as a relic. The provenance of this information was also of the first order, as Bede had heard it from the Abbot of Dacre himself, one Thrydred. The site then disappears into the mists of time until the twelfth century, when William of Malmesbury claimed that at least part of the events surrounding the meeting in 927 between King Æthelstan, the first of the Wessex line to call himself Rex Anglorum (King of the English), and the kings of the nascent polity of the Scots, Welsh, and the Lords of Bamburgh, the rump of the once-great Northumbrian kingdom, took place at Dacre, where the son of

Constantine, King of Scots, was baptised ‘at the sacred font’. In the D recension of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, this is recorded as having taken place aet Aemotum, ‘at the Eamont’, the river that flows about a mile (1.6 km) to the east of Dacre, from Ullswater, past Penrith and the Roman fort of Brougham, before its confl uence with the River Eden.

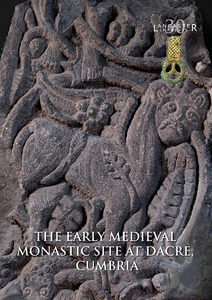

Physical evidence to support this provenance came from the fi nding of very high-quality early medieval sculptural

fragments in and around the church in the nineteenth- and early twentieth centuries, one fragment of a crossshaft

of early ninth-century date being unusual in having human fi gures climbing amongst the vinescroll on the main face, as well as an exotic beast, a ‘lion’, amongst the foliage. This clearly forms part of the great tradition of Northumbrian stone sculpture. The other, slightly later, tenth-century slab, when found built into the east wall of the chancel of the medieval church in 1875, was thought to depict the events recorded by William of Malmesbury, and is thus called the Dacre Stone. The iconography, depicted in the Anglo-Scandinavian style of that period in Northumbria, has been reinterpreted as depicting not just Adam and Eve, with the apple tree and serpent, but also the sacrifice of Isaac, rather than the baptism of the king’s son, but nevertheless, the sophistication of this is marked. In addition, a drain emerging from the southern boundary of the medieval churchyard was excavated in the 1920s, which was thought to be part of this early monastic site.

The opportunity to examine such an important site came in 1982, when permission was granted to build a house in the plot of land immediately to the west of the churchyard. It was also noticed that there were earthworks to the north and east of a modern northern extension to the churchyard, which seemed to have been aff ected by this. Excavations therefore took place in the Orchard to the west of the churchyard, and in the northern churchyard extension, the latt er between 1982 and 1985, when the drain in the southern churchyard was also re-excavated.

The northern churchyard proved to be the site of an extensive early cemetery, containing over 200 graves,

though the leached condition of the soils meant that bone survival was minimal. Many of these graves, however, contained iron chest fi tt ings, of a type recognised at a growing number of Northumbrian burial sites of the seventh- to ninth centuries. These seemed to have been focused on something, presumably a church, to the south, on the approximate position of the medieval parish church. Unusually, there was clear evidence of a western boundary to this cemetery, beyond which were at least two buildings, one a rectangular post-built structure of a type increasingly associated with early medieval Northumbria. The other was more unusual, with an apparently rounded eastern end, the only part within the excavation. This was associated with two hearthstones, one a reused millstone, and a wealth of early medieval material, including pins, buckles, and strap-ends, spindle whorls, and loomweights, and vessel and window glass.

Early ditches were excavated in the south of the churchyard, and to the west, in the Orchard, which seemed to have been followed when the medieval churchyard was established. In the southern churchyard, this ditch was overlain by the substantial stone drain, fi rst excavated in the 1920s, which proved to have been constructed of reused Roman stones, perhaps from a bridge or mill. This seemed to have served two foci to the north, and could be traced in the fi eld to the south, curving in a south-easterly direction through further earthworks. In the Orchard, the primary ditch was also sealed by a stone structure, apparently the north-western corner of a building, now wholly and tantalisingly lost beneath the churchyard.

It is likely that the centre of monastic activity was within the medieval churchyard, as has been recorded at the monastic sites of Wearmouth and Jarrow in the North East, but whilst the monastery had clearly been established by 731, when the Historia Ecclesiastica was completed, there was no obvious evidence for when it ceased to exist. The datable artefacts fit well within an eighth- to ninth-century context, yet the Dacre Stone, with its sophisticated iconography, is clearly later than this floruit, seemingly of tenth-century date. The cemetery showed signs of erosion, in that the graves were shallow, as though it had fallen out of use before the medieval churchyard was established. This was seen physically in the form of a bank and ditch that had cut through the early cemetery, only some 6 m to the north of the medieval church, the bank sealing many of the shallow

graves. Subsequently, in the earlier thirteenth century, a wall was constructed on the crest of the bank, and this

stood as the northern churchyard boundary until about 1950.

A very similar stretch of wall in the Orchard to the west was probably part of the same feature. Built against its

interior face was a small building, probably of thirteenth- or fourteenth-century date, which would explain the peculiar shape of the churchyard at that point. It is tempting to see this as connected with the church, perhaps to house the Parish priest.

Perhaps ironically, the earthworks that led to the excavations in the northern churchyard did not prove to be

early medieval in date, but were instead evidence of a medieval farmstead immediately beyond the churchyard, apparently accessed from a hollow-way, visible in the fi eld to the east. This consisted of at least three buildings,

all apparently of timber. That to the east was probably the domestic accommodation, as the south gable had been rebuilt to incorporate a fi replace, while that to the west was probably a barn, and the northernmost structure, with a stone fl oor and drain, was probably to house animals. This seems to have fallen out of use by the fifteenth century, when the village either shrank or moved to its present site to the west of the churchyard. Dacre then remained as it does today, a small village away from the main routeways, both ancient and modern, with an important hidden history of the part it played in the development of the modern country.

| Item Type: | Monograph (UNSPECIFIED) |

|---|---|

| Subjects: | Geographical Areas > English Counties > Cumbria Period > UK Periods > Early Medieval 410 - 1066 AD |

| Divisions: | Oxford Archaeology North |

| Depositing User: | Parsons |

| Date Deposited: | 11 Jan 2022 13:36 |

| Last Modified: | 01 Jun 2023 08:13 |

| URI: | http://eprints.oxfordarchaeology.com/id/eprint/6183 |